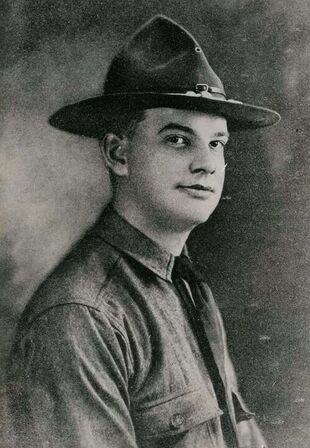

Sergeant Joyce Kilmer was 31 years-old in 1918 when he died in battle in the First World War. To honor his memory, the American Legion preserved his childhood home in New Brunswick, New Jersey. The city renamed the street in front of the house "Joyce Kilmer Avenue." And across the country, commemorative parks opened in Brooklyn, the Bronx, North Carolina and all over the world.

Joyce Kilmer's wife, on the other hand, burned all of their private letters, thereby shielding their relationship from a public that was quick to view her husband as a martyr.

Join Thinkery & Verse, the New Brunswick Historical Association, and the New Brunswick Historical Society on an exploration of the memories and meanings of the Joyce Kilmer House, the childhood home of the internationally famous poet and war writer.

Joyce Kilmer's wife, on the other hand, burned all of their private letters, thereby shielding their relationship from a public that was quick to view her husband as a martyr.

Join Thinkery & Verse, the New Brunswick Historical Association, and the New Brunswick Historical Society on an exploration of the memories and meanings of the Joyce Kilmer House, the childhood home of the internationally famous poet and war writer.

|

The Joyce Kilmer House is located at 17 Joyce Kilmer Avenue in New Brunswick, New Jersey. It is a modest home with modest origins. The back half of the structure was built in 1780 as a postcolonial farmhouse; in its current urban environment, it takes some imagination to stand across the street from the home and visualize it surrounded by farmland. The front half of the house was built in the mid-1800s, and greatly resembles other New Brunswick houses from that time period.

Joyce Kilmer was born in this house in 1886, and he was baptized and confirmed at Christ Church, just a few blocks away. His father was a chief researcher for Johnson & Johnson. The family only lived in the house for a few years before moving to a larger residence on College Avenue. Still, the romanticism of Kilmer's poetry had combined with the romantic notion of a 'war to end all wars', and this was enough to provoke the local American Legion into establishing the house as a meeting place from 1929 onwards. In a way, the plainness of the house stands as rebuke of the awfulness of death in the First World War. The war claimed more than 50,000 American lives, and at least 15 million worldwide. It is now owned by the State of New Jersey, and leased by the City of New Brunswick. |

Joyce Kilmer's influence on popular culture stemmed not exclusively from his wartime service, but from a poem he published several years earlier -- "Trees". Written in iambic four-foot couplets, the simple twelve-line poem's publication coincided with one of the first waves of American interest in the preservation of natural spaces. Kilmer continues to have a popular following, and blogs, discussion boards, and newsletters demonstrate that many Americans continue to reflect on his work.

Shortly after its publication, the poem's brevity enabled its adoption into the new mediums of recorded music and television:

Shortly after its publication, the poem's brevity enabled its adoption into the new mediums of recorded music and television:

"Trees" by Joyce Kilmer

|

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree. A tree whose hungry mouth is prest Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast; A tree that looks at God all day, And lifts her leafy arms to pray; A tree that may in Summer wear A nest of robins in her hair; Upon whose bosom snow has lain; Who intimately lives with rain. Poems are made by fools like me, But only God can make a tree. [Sheet music by Oscar Rasbach available at the Sheldon Harris Collection at the University of Mississippi.] |

|

|

|

The poem continues to receive new interpretations.

People around the world, for example, recite the poem while learning English. Teachers exploit it as a mimetic tool for learning vowel sounds. Legal scholar Jennifer Davis even uncovered instances in which the poem has been respectfully parodied in legal arguments. |

In a darker vein--and perhaps in the spirit of preserving Kilmer House as a war memorial--Christopher Edwin Steininger and Patronoid Magazine offer a video-graphic interpretation of the poem that contrasts Kilmer's violent death with the romantic innocence of his writing:

An earlier animated interpretation takes a softer approach, and makes an explicit connection between Kilmer's Christian faith and the imagery of the poem.

|

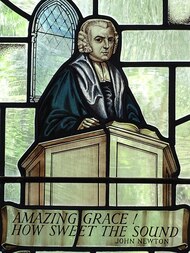

By drawing on Christian traditions, the poem exists in the same symbolic space as John Newton's classic hymn, "I saw One hanging on the tree".

In this literature, the tree becomes a synonym for the wooden cross upon which Jesus Christ is crucified. |

I saw One hanging on a tree,

In agony and blood; He fixes His loving eyes on me, As near His cross I stood. O, can it be, upon a tree The Savior died for me? My soul is thrilled, my heart is filled, To think He died for me! |

The resonances with hymn grant Kilmer's panegyric lines a more visceral reading. Now, a tree that praises God with "her leafy arms" is also a tree upon which Christ can die "In agony and blood". The juxtaposition enables Kilmer's gendered, anthropomorphized tree both to praise Kilmer's God and to serve as the instrument of His death and sacrifice.

The implicit sacrifice in "Trees" would become explicit in Kilmer's war poetry, all of which follows in the same panegyric style.

The implicit sacrifice in "Trees" would become explicit in Kilmer's war poetry, all of which follows in the same panegyric style.

|

Here for example is Joyce Kilmer's "Prayer of a Soldier in France", a poem in which an infantryman suffering through trench warfare mitigates his own discomfort by imagining the suffering of Jesus Christ.

|

My shoulders ache beneath my pack

(Lie easier, Cross, upon His back). I march with feet that burn and smart (Tread, Holy Feet, upon my heart). Men shout at me who may not speak (They scourged Thy back and smote Thy cheek). I may not lift a hand to clear My eyes of salty drops that sear. (Then shall my fickle soul forget Thy agony of Bloody Sweat?) My rifle hand is stiff and numb (From Thy pierced palm red rivers come). Lord, Thou didst suffer more for me Than all the hosts of land and sea. So let me render back again This millionth of Thy gift. Amen. |

Given the Christian tone of much of his poetry, it is is perhaps not surprising that members of Joyce Kilmer's adopted faith, Catholicism, tend to offer the most frequent reappraisals of his poetic work. Many of these appraisals appeared immediately after his death, and they have continued up to the present time.

Meanwhile, veterans organizations draw attention to Joyce Kilmer's military service, and his fall on the battlefield. The local American Legion, Post 25, is still named in his honor. And it is a rare Memorial Day that passes without a heartfelt reminder of Joyce Kilmer's death.

Meanwhile, veterans organizations draw attention to Joyce Kilmer's military service, and his fall on the battlefield. The local American Legion, Post 25, is still named in his honor. And it is a rare Memorial Day that passes without a heartfelt reminder of Joyce Kilmer's death.

The strident effort to memorialize the dead leads to the preservation of such a building as the Joyce Kilmer House. The American Legion, a veterans organization, bought the house in 1929, just eleven years after the end of the war. They continued to use it until 1972.

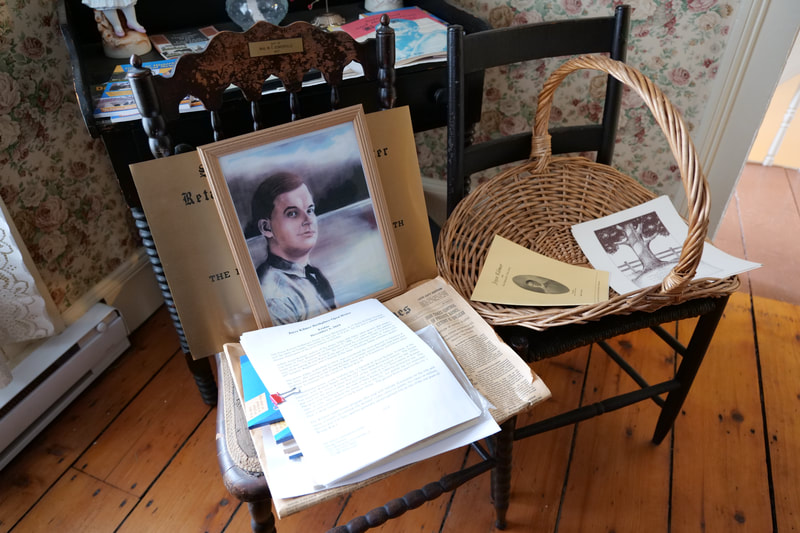

Today, the house remains open to the public. The first floor has been renovated for use by the 'Dial-a-Ride' community program that provides transportation to the elderly and disabled. The second floor looks much as the American Legion left it in 1972. At the dedication of the memorial in 1930, the Reverend Herbert Parrish, rector of Christ Church, described it as the "Joyce Kilmer Shrine," and the small mementos and treasures filling the rooms certainly reflect that purpose. For many years, New Brunswick's City Historian, George Dawson, has offered tours of the house each December, but in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted this annual observance.

Today, the house remains open to the public. The first floor has been renovated for use by the 'Dial-a-Ride' community program that provides transportation to the elderly and disabled. The second floor looks much as the American Legion left it in 1972. At the dedication of the memorial in 1930, the Reverend Herbert Parrish, rector of Christ Church, described it as the "Joyce Kilmer Shrine," and the small mementos and treasures filling the rooms certainly reflect that purpose. For many years, New Brunswick's City Historian, George Dawson, has offered tours of the house each December, but in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted this annual observance.

|

But people have different ways of remembering the dead, especially when they view their loved one not in a single instance of sacrifice, but in the full richness of life. When looking at the birthplace of Joyce Kilmer, it can also be enlightening to consider the family that was still to come--his own wife and children; this is the family that he would leave behind to go to war.

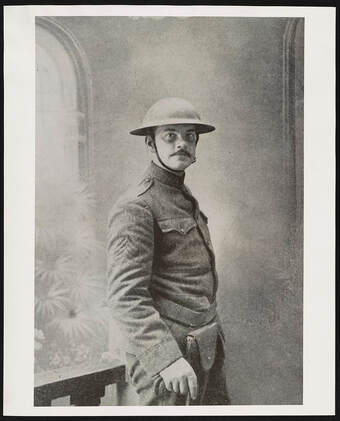

When Joyce chose to join the infantry, his writing career was in full bloom and his family was in crisis. He was already a widely published poet and literary critic, but his youngest child, Rose, was dying of polio. Instead of seeking an officer's commission commensurate with his class and education, he enlisted as a private soldier, and then sought the help of a military chaplain to ensure he would get assigned to a frontline unit, the famous "Fighting 69th" led by Bill Donovan. |

|

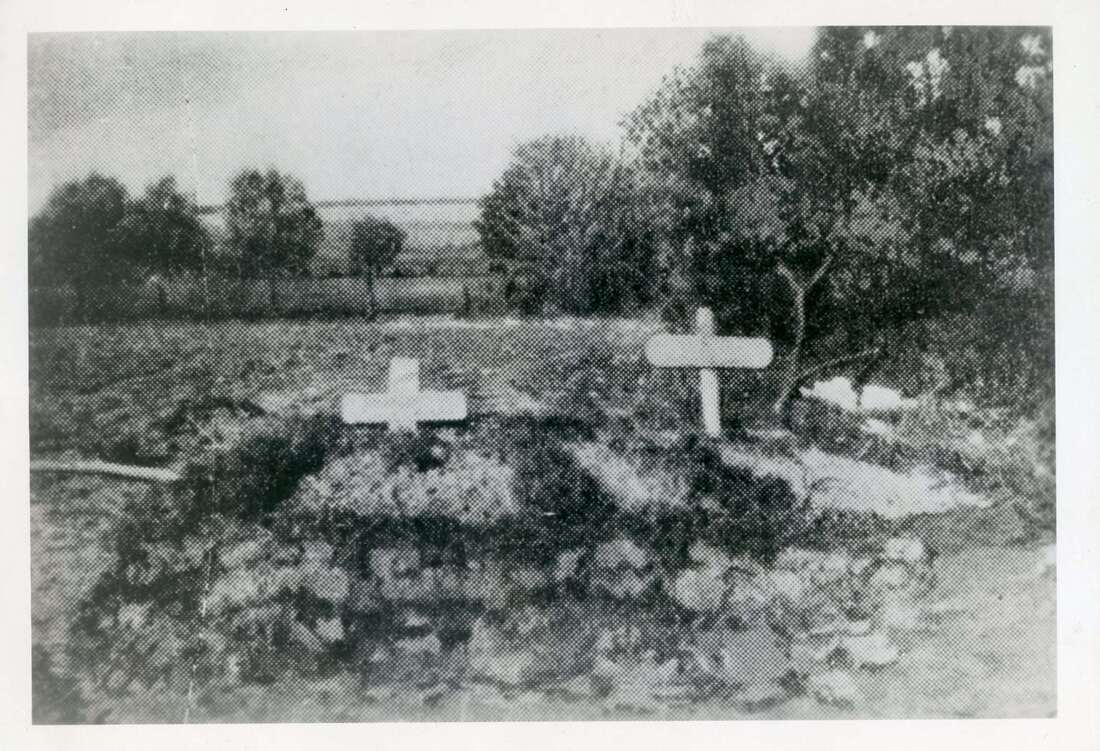

It was in the service of this unit that Sergeant Joyce Kilmer crawled up a ridgeline to scout an enemy position in the Second Battle of the Marne; according to Donovan, a machine-gun bullet immediately tore through Kilmer's skull (some say it was a sniper). He was buried close to where he fell. Kilmer was among some 50,000 Americans killed in the campaign.

In the century that followed the end of World War One, America has gone through several re-evaluations of the conflict. The centennial of the armistice in 2018 encouraged many reexaminations of the literature as well. One of the voices recently lifted was that of Aline Murray Kilmer, Joyce Kilmer's widow. In his study of Aline Murray Kilmer's work for the WWrite blog at the World War One Centennial Commission, scholar and military veteran Peter Molin drew special attention to the inevitable tensions between duty to family and duty to country.

"It’s not impossible to imagine that Aline was unhappy with Joyce’s decision to join the Army at age 30 at a lower salary than he was making as an author and speaker, not to mention leaving her at home with five children. When Joyce was asked how his wife felt about his decision to leave his career and family to fight in France, he reportedly replied “She’s game.” In light of Rose’s death and Joyce’s imminent one, Aline’s feelings must have been more complex." That complexity is reflected in Aline Murray Kilmer's poetry, which is very different from her husband's. His vigorous couplets give way to a prosody of inward reflections, and a haunted irony that underlines not the glory of dying in war, but the damage of living. New Jersey pastoralism and nostalgia are still present, but twisted with a pain that is entirely human. As Molin points out, a sense of personal regret and private obsession runs through her poetry. The following three poems, selected from a large body of work, offer a sense of Aline's poetry.

The first, "Bound," has rhetorical echoes of W. B. Yeats famous love poem, "When You Are Old." The speaker identifies herself as an object of desire, and tells the "faithless" listener (Joyce Kilmer?) that her "coldness" towards him will not drive her memory away from him, but will instead burrow deeper into his heart. |

|

"BOUND," by Aline Murray Kilmer.

If I had loved you, soon, ah, soon I had lost you.

Had I been kind you had kissed me and gone your faithless way.

The kiss that I would not give is the kiss that your lips are holding:

Now you are mine forever, because of all I have cost you.

You think that you are free and have given over your sighing,

You think that from my coldness your love has flown away:

But mine are the hands you shall dream that your own are holding,

And mine is the face you shall look for when you are dying.

If I had loved you, soon, ah, soon I had lost you.

Had I been kind you had kissed me and gone your faithless way.

The kiss that I would not give is the kiss that your lips are holding:

Now you are mine forever, because of all I have cost you.

You think that you are free and have given over your sighing,

You think that from my coldness your love has flown away:

But mine are the hands you shall dream that your own are holding,

And mine is the face you shall look for when you are dying.

The second poem, "Shards", conjures images of destruction wrought from self-abnegation.

|

"SHARDS," by Aline Murray Kilmer

I can never remake the thing I have destroyed; I brushed the golden dust from the moth’s bright wing, I called down wind to shatter the cherry-blossoms, I did a terrible thing. I feared that the cup might fall, so I flung it from me; I feared that the bird might fly, so I set it free; I feared that the dam might break, so I loosed the river: May its waters cover me. |

|

Aline's summoning and shattering of "cherry-blossoms" brings to mind a poem from another New Jersey native, William Carlos Williams -- "The Widows' Lament in Springtime."

The next poem included here, 'Tribute' is dedicated to Michael, a son who died in childhood. It her extant work, there does not seem to be an elegy that addresses her husband's death in such a direct way.

The next poem included here, 'Tribute' is dedicated to Michael, a son who died in childhood. It her extant work, there does not seem to be an elegy that addresses her husband's death in such a direct way.

|

"TRIBUTE," by Aline Murray Kilmer

Deborah and Christopher brought me dandelions, Kenton brought me buttercups with summer on their breath, But Michael brought an autumn leaf, like lacy filigree, A wan leaf, a ghost leaf, beautiful as death. Death in all loveliness, fragile and exquisite, Who but he would choose it from all the blossoming land? Who but he would find it where it hid among the flowers? Death in all loveliness, he laid it in my hand. |

|

Perhaps Aline's most direct expression of love and frustration with her husband comes from her poem "Tour de Force," a piece that was published in Vigil in 1921. In a contemporaneous review in The New Republic, Louis Untermeyer assumed that the poem was "self-satire." It is satire alright, but probably of her late husband's "The Peacemaker."

Joyce's "Peacemaker" is one of the most earnest expressions of American wartime idealism. Rather than using its irony to criticize the war, his Petrarchan sonnet instead seems to celebrate the paradoxes of Christian militarism.

There are several clues in Aline's poem that suggest she is responding to her deceased husband. In the title of Aline's "Tour de Force," notice the use of a clichéd French phrase; the title alludes to the geographic location of her husband's death, but it is also a reference to the vigor of his language. The poem adopts her husband's voice, but lightens the use of rhyme: Joyce's chain/stain/pain/gain (almost a collection of sports clichés) gives way to the simple echo of Aline's "pain/again." In her own poem, she has transformed Joyce's sonnet for a dead soldier into a "little song" woven from pain. His sonnet is striking and memorable, and therefore Aline suggests "You may take it with you". Joyce, however, "shall not sing it again" but if the listener has "learned it through" then "It will keep you brave and strong." Though Joyce's sonnet may empower the listener, Aline offers a devastating final appraisal: "There is not a word of it true."

Aline may have burned all of their private letters, but she nevertheless left us a striking correspondence. "Tour de Force" quietly selects its target, but nevertheless it is the most forceful poetic response of a wife to her husband's writing in American English.

"Tour de Force" echoes the posture of the Joyce Kilmer House itself: a home-front shrine dedicated to a battlefield death.

There are several clues in Aline's poem that suggest she is responding to her deceased husband. In the title of Aline's "Tour de Force," notice the use of a clichéd French phrase; the title alludes to the geographic location of her husband's death, but it is also a reference to the vigor of his language. The poem adopts her husband's voice, but lightens the use of rhyme: Joyce's chain/stain/pain/gain (almost a collection of sports clichés) gives way to the simple echo of Aline's "pain/again." In her own poem, she has transformed Joyce's sonnet for a dead soldier into a "little song" woven from pain. His sonnet is striking and memorable, and therefore Aline suggests "You may take it with you". Joyce, however, "shall not sing it again" but if the listener has "learned it through" then "It will keep you brave and strong." Though Joyce's sonnet may empower the listener, Aline offers a devastating final appraisal: "There is not a word of it true."

Aline may have burned all of their private letters, but she nevertheless left us a striking correspondence. "Tour de Force" quietly selects its target, but nevertheless it is the most forceful poetic response of a wife to her husband's writing in American English.

"Tour de Force" echoes the posture of the Joyce Kilmer House itself: a home-front shrine dedicated to a battlefield death.

|

Joyce Kilmer's "THE PEACEMAKER"

Upon his will he binds a radiant chain, For Freedom’s sake he is no longer free. It is his task, the slave of Liberty, With his own blood to wipe away a stain. That pain may cease, he yields his flesh to pain. To banish war, he must a warrior be. He dwells in Night, eternal Dawn to see, And gladly dies, abundant life to gain. What matters Death, if Freedom be not dead? No flags are fair, if Freedom’s flag be furled. Who fights for Freedom, goes with joyful tread To meet the fire of Hell against him hurled, And has for captain Him whose thorn-wreathed head Smiles from the Cross upon a conquered world. |

Aline Murray Kilmer's "TOUR DE FORCE"

Smilingly, out of my pain, I have woven a little song; You may take it away with you. I shall not sing it again, But when you have learned it through It will keep you brave and strong. I wove it out of my pain: There is not a word of it true. |

The Joyce Kilmer House:

A unique opportunity for reflection

New Brunswick's war memorials include parks, plazas, statues, street signs, and more, though New Brunswick is not an especially martial part of the country. Most of the local military bases have closed down. The World War Two depot Camp Kilmer is now a part of Rutgers University, and a popular nature preserve. The various memorials persevere, often because each generation renews its concern for the sons and daughters of the city that gave up their lives long ago. Each type of memorial brings light to a different aspect of the relationship between war and society.

Street signs are often dedicated to fallen soldiers, and emphasize each individual's sacrifice. The streets in Robeson Village, for example, are named after African American soldiers killed or wounded in World War Two.

Street signs are often dedicated to fallen soldiers, and emphasize each individual's sacrifice. The streets in Robeson Village, for example, are named after African American soldiers killed or wounded in World War Two.

| robeson_village_street_names_-_nbhs.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2423 kb |

| File Type: | |

On the other side of town, the statues in Monument Square echo canonical gestures from past centuries of military memorials. At the intersection of Livingston and George Street, for example, we can see Colonel Neilson reading the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the symbolism of which is complicated by Nielson's personal reliance on enslaved labor. On a high neoclassical plinth, we also see a nameless sergeant holding the Union flag in the American Civil War; his anonymity quietly stands in for the more than 360,000 Union dead from that conflict, and the more than 2 million who took up arms.

|

The preservation of the house at 17 Joyce Kilmer Avenue is less classically heroic. It is more personal. It reminds us that Sergeant Joyce Kilmer came from a family, and that he left a family behind. The house's intimate simplicity is perhaps a little more humane than the bronze and marble epitaphs which we most often dedicate to fallen soldiers. In this way, the Joyce Kilmer House is entirely unique among the war memorials of New Brunswick and Middlesex County.

|

Grant funding for this project has been provided by the Middlesex County Board of County Commissioners through a grant award from the Middlesex County Cultural and Arts Trust Fund.

Additional funding was provided by Thinkery & Verse L.L.C.

Additional funding was provided by Thinkery & Verse L.L.C.

|

This site was created for the New Brunswick Historical Association and the New Brunswick Historical Society by Thinkery & Verse LLC. © 2021. The "Joyce Kilmer House digital tour" is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The historical and literary analysis were conducted by Dr. J. M. Meyer, the co-artistic director of Thinkery & Verse, and a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Photography and videography were by Rafael Manzanares. Special thanks to Bob Belvin, Elizabeth Ciccone, George Dawson, Susan Mollica, and Brian Smith for their inspiration and guidance. Special thanks to Hope Vega for providing access to the Joyce Kilmer House. The Joyce Kilmer House 17 Joyce Kilmer Avenue New Brunswick, New Jersey |

WARNING: the links on this page lead to third-party content. The links are not monitored or controlled by Thinkery & Verse, and some may contain advertisements or unrelated material.